Should writers shy away from mentioning skin color?

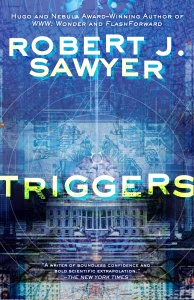

by Rob - July 13th, 2012.Filed under: Triggers, Writing.

An email I recently received said, “I just started your novel Triggers and was wondering why you repeatedly point out that one character is black and another is white. I am not criticizing the book; I only find it unusual and had not seen anything like this before.”

My reply:

I’ve done it in most of my books. It’s my response to the usual technique, which I find racist and offensive, of only mentioning the color of skin when it isn’t white. That is, when you say you’ve never seen anything like this before, what you almost certainly mean is you’ve never seen it mentioned when a character is white before; there are thousands upon thousands of novels that do point out skin color — but only when it isn’t white. And to me, that’s wrong.

To me, it’s silly to describe eye color, hair color, shirt color, and so on, and pretend that no one in the scene would have noticed skin color (indeed, if a police officer asked you to describe a person, and you provided any of those other details but feigned “not to have noticed” the color of the skin, you would not be believed, nor should you be).

In fact, I address the issue directly, in my novel Watch, where I write:

Caitlin’s friend Stacy was black, and Caitlin had often heard people trying to indicate her without mentioning that fact, even when she was the only African-American in the room. They’d say things to people near Caitlin like, “Do you see that girl in the back — the one with the blue shirt? No, no, the other one with the blue shirt.” Caitlin used to love flustering them by saying, “You mean the black girl?” It had tickled both her and Stacy, showing up this “suspect delicacy” as Stacy’s mom put it.

That “suspect delicacy” interests me a great deal. Obviously, no one would suggest that filmmakers or TV producers should wash out the colors on their productions to remove the skin color of people; why should novelists be so coy as to not mention it? Or why should they be forced to use euphemisms, which are often contrived (“she was sporting a nice tan;” “his dreadlocks flew behind him as he ran”), or lapse into often offensively stereotypical dialect to convey race?

Obviously, skin color — and eye color, and hair color, and the color of one’s shirt, and the color of one’s shoes — doesn’t define who one is, but it does in part describe the person, and my job is to describe reality. My characters live in a multicultural world, and my fiction celebrates that diversity. Indeed, as you’ll see later in Triggers, I write:

He looked left and right, recognized left, and headed that way, and — ah! — there it was, a door painted in a pinkish beige that his old pencil-crayon set had called, back in the days of easy racism, “flesh.”

Also, you might find it interesting to google the discussion of the casting of African-Americans in roles for the movie version of The Hunger Games. Novelist Suzanne Collins was not, for many readers, specific enough in her character descriptions, and that allowed demonstrably racist readers to people her story in their heads with an all-white cast, something she never intended, and something those racist readers had a hard time dealing with when the books were brought to the screen. Here’s an example.

I prefer to vividly celebrate all the wonderful variety of humanity. As BookBanter‘s review of Triggers said, “Sawyer should be applauded for a wonderfully diverse cast, as readers are immediately introduced to a powerful female secret service agent, an impressive African-American female doctor who is the president’s primary physician, and the interesting Dr. Singh, who is actually Canadian, which is Sawyer’s own nationality.”

All best wishes.

My original correspondent replied: “Thanks for taking the time to answer my e-mail, truth be told, I didnt expect one. I now see it from your point of view and agree with your approach.”

This fine fellow wasn’t the first to ask about this (although it doesn’t come up often). For those who are curious, here’s the opening scene of Triggers, in which the skin color of four characters is noted in some way, two white, two black; I stand by my contenion that this wouldn’t have raised a single eyebrow if I’d only mentioned, as so many other books do, the skin color of the African-American characters.

Susan Dawson — thirty-four, with pale skin and pale blue eyes — was standing behind and to the right of the presidential podium. She spoke into the microphone hidden in her sleeve. “Prospector is moving out.”“Copy,” said the man’s voice in her ear. Seth Jerrison, white, long-faced, with the hooked nose political cartoonists had such fun with, strode onto the wooden platform that had been hastily erected in the center of the wide steps leading up to the Lincoln Memorial.

Susan had been among the many who were unhappy when the president decided yesterday to give his speech here instead of at the White House. He wanted to speak before a crowd, he said, letting the world see that even during such frightening times, Americans could not be cowed. But Susan estimated that fewer than three thousand people were assembled on either side of the reflecting pool. The Washington Monument was visible both at the far end of the pool and upside down in its still water, framed by ice around the edges. In the distance, the domed Capitol was timidly peeking out from behind the stone obelisk.

President Jerrison was wearing a long navy-blue coat, and his breath was visible in the chill November air. “My fellow Americans,” he began, “it has been a full month since the latest terrorist attack on our soil. Our thoughts and prayers today are with the brave people of Chicago, just as they continue to be with the proud citizens of San Francisco, who still reel from the attack there in September, and with the patriots of Philadelphia, devastated by the explosion that shook their city in August.” He briefly looked over his left shoulder, indicating the nineteen-foot-tall marble statue visible between the Doric columns above and behind him. “A century and a half ago, on the plain at Gettysburg, Abraham Lincoln mused about whether our nation could long endure. But it has endured, and it will continue to do so. The craven acts of terrorists will not deter us; the American spirit is indomitable.”

The audience — such as it was — erupted in applause, and Jerrison turned from looking at the teleprompter on his left to the one on his right. “The citizens of the United States will not be held hostage by terrorists; we will not allow the crazed few to derail our way of life.”

More applause. As she scanned the crowd, Susan thought of the speeches by previous presidents that had made similar claims. But despite the trillions spent on the war on terror, things were getting worse. The weapons used for the last three attacks were a new kind of bomb: they weren’t nukes, but they did generate super-high temperatures and their detonation was accompanied by an electromagnetic pulse, although the pulse was mostly free of the component that could permanently damage electronics. One could conceivably guard against the hijacking of airplanes. But how did one defend against easily hidden, easily carried, hugely powerful bombs?

“Each year, the foes of liberty gain new tools of destruction,” continued Jerrison. “Each year, the enemies of civilization can do more damage. But each year we — the free peoples of the world — gain more power, too.”

Susan was the Secret Service agent-in-charge. She had line-of-sight to seventeen other agents. Some, like her, were standing in front of the colonnade; others were at the sides of the wide marble staircase. A vast pane of bulletproof glass protected Jerrison from the audience, but she still continued to survey the crowd, looking for anyone who seemed out of place or unduly agitated. A tall, thin man in the front row caught her eye; he was reaching into his jacket the way one might go for a holstered gun — but then he brought out a smartphone and started thumb-typing. Tweet this, asshole, she thought.

Jerrison went on: “I say now, to the world, on behalf of all of us who value liberty, that we shall not rest until our planet is free of the scourge of terrorism.”

Another person caught Susan’s attention: a woman who was looking not at the podium, but off in the distance at — ah, at a police officer on horseback, over by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

“Before I became your president,” Jerrison said, “I taught American history at Columbia. If my students could take away only a single lesson, I always hoped it would be the famous maxim that those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it—”

Ka-blam!

Susan’s heart jumped and she swung her head left and right, trying to spot where the shot had come from; the marble caused the report to echo. She looked over at the podium and saw that Jerrison had slammed forward into it — he’d been shot from behind. She shouted into her sleeve microphone as she ran, her shoulder-length brown hair flying. “Prospector is hit! Phalanx Alpha, shield him! Phalanx Beta, into the memorial — the shot came from there. Gamma, out into the crowd. Go!”

Jerrison slid onto the wooden stage, ending up face down. Even before Susan had spoken, the ten Secret Service agents in Phalanx Alpha had formed two living walls — one behind Jerrison to protect him from further shots from that direction; another in front of the bulletproof glass that had shielded him from the audience, in case there was a second assailant on the Mall. A male agent bent down but immediately stood up and shouted, “He’s alive!”

The rear group briefly opened their ranks, letting Susan rush in to crouch next to the president. Journalists were trying to approach him — or at least get pictures of his fallen form — but other agents prevented them from getting close.

Alyssa Snow, the president’s physician, ran over, accompanied by two paramedics. She gingerly touched Jerrison’s back, finding the entrance wound, and — presumably noting that the bullet had missed the spine — rolled the president over. The president’s eyes fluttered, looking up at the silver-gray November sky. His lips moved slightly, and Susan tried to make out whatever he was saying over the screams and footfalls from the crowd, but his voice was too faint.

Dr. Snow — who was an elegant forty-year-old African American — soon had the president’s long coat open, exposing his suit jacket and blood-soaked white shirt. She unbuttoned the shirt, revealing the exit wound; on this cold morning steam was rising from it. She took a length of gauze from one of the paramedics, wadded it up, and pressed it against the hole to try to stanch the flow of blood. One paramedic was taking the president’s vital signs, and the other now had an oxygen mask over Jerrison’s mouth.

“How long for a medical chopper?” Susan asked into her wrist.

“Eight minutes,” replied a female voice.

“Too long,” Susan said. She rose and shouted, “Where’s Kushnir?”

“Here, ma’am!”

“Into the Beast!”

“Yes, ma’am!” Kushnir was today’s custodian of the nuclear football — the briefcase with the launch procedures; he was wearing a Navy dress uniform. The Beast — the presidential limo — was five hundred feet away on Henry Bacon Drive, the closest it could get to the memorial.

The paramedics transferred Jerrison to a litter. Susan and Snow took up positions on either side and ran with the paramedics and Phalanx Alpha down the broad steps and over to the Beast. Kushnir was already in the front passenger seat, and the paramedics reclined the president’s rear seat until it was almost horizontal, then moved him onto it.

Dr. Snow opened the trunk, which contained a bank of the president’s blood type, and quickly set up a transfusion. The doctor and the two paramedics took the rearward-facing seats, and Susan sat beside the president. Agent Darryl Hudkins — a tall African American with a shaved head — took the remaining forward-facing chair.

Susan pulled her door shut and shouted to the driver, “Lima Tango, go, go, go!”

Robert J. Sawyer online:

Website • Facebook • Twitter • Newsgroup • Email

July 19th, 2012 at 5:22 pm

Interesting perspective. Being a new Sawyer fan (I recently finished Wake) I certainly did not notice (hence did not have any issue) and mention of race etc. I have seen instances here in the States where someone will describe someone in every way possible until it becomes necessary to mention that they are black, hispanic, etc. But with people I personally know who do it that is because they are trying to avoid using the race description because they feel that in doing so they are singling out that attribute and do not want to appear racist.

Concerning “The Hunger Games” I have read and loved all of them! I guess I never realized until now that the author did not really mention race. I guess that for me in many instances race is no more important for me to know than shoe size, unless race somehow comes into play. I am not sure if people would think that racist, color blind or simply indifferent.

July 20th, 2012 at 11:40 pm

Suzanne Collins made one of your points for you, Robert. She describes Rue (Ch. 7 of “The Hunger Games”): “She has dark brown eyes and satiny brown skin.” Euphemism. But, in her defense, this may be a future where racial terminology matters far less than the class distinctions of the Districts in which citizens live.

So:

First, I completely agree with you. It is not racist to point out hair, eye or skin color or any other physical attribute. These are attributes. The conclusions drawn from the presence (or absence) of a physical attribute are where the racism resides. (“White men can’t jump,” for example.)

Second, are we now so guilty or suspicious of how we have internalized our own observations of those around us as to be cautious of all race-differentiating attributes in text?

July 24th, 2012 at 6:01 pm

Isn’t it also in TRIGGERS where you discuss the mental image people get of another, in their memory — and it only includes that which is different than them? So the white people don’t store ‘white’ in their mental image, and black people don’t store ‘black’ in theirs?

Could it be that aspect of it that causes it to jump off the page for a white reader who is used to filling in their mental image of the person as if they are recalling them?